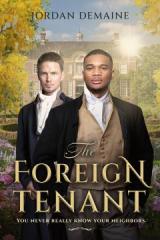

The Foreign Tenant

CLARESHOLM HALL’S new tenant came to town with all the subtlety of a runaway circus elephant Thomas once read about in the Times.

“He’s dismissed all the servants but the kitchen staff. And he’s French,” Papa said at the breakfast table one morning, in a tone another man might use to call a man a thieving bounder and all-around cur.

“Belgian, I heard, dear,” Mama replied, delicately spearing her sliced tomato.

Papa was unmoved. “Near as. What’s old Pryce thinking, letting his place to a foreigner?”

“I think it’s nice to have a little bit of the exotic in the area,” Alice put in, ignoring the fact, as the family always did, that Thomas was himself as exotic a man as Brackenridge had seen in decades, in ways both glaringly obvious as well as more hidden.

“We should have him around for tea,” Mama persisted. “It would be the neighborly thing to do.”

Papa scoffed. “No Frenchman is setting foot in my house.”

“He’s Belgian, Horatio.”

“So,” Papa said, in a tone that indicated the conversation was closed, “is King Leopold.”

Alice caught Thomas’s eye over the table. King Leopold? she mouthed, eyebrows raised to her hairline. Thomas smiled and picked up the newspaper, grateful that breakfast was the only time he was permitted to read at the table.

Later that morning, Alice found Thomas sitting in his favorite corner of the library. She was dressed to go out, wearing her hat and with her gloves in her hand.

“Papa is an awful bore sometimes.” She pulled on a glove.

“You know I won’t say anything against him.”

“Yes, I know. Because you’re a dreadfully good son and I’m a terribly ungrateful daughter.”

“I don’t think you’re ungrateful.” But her position here was her birthright. Alice was the natural daughter of Horatio Carrington, fourteenth Earl of Montescue, and his wife. She was their only child. Thomas was the half-Negro, American-born by-blow, the worst mistake ever made by the Earl’s youngest sister. By all accounts, she was prone to them. The Earl and his wife brought their nephew to England and took him in out of Christian charity. Thomas could easily have been consigned to an orphanage on the other side of the Atlantic. Lord and Lady Montescue had always been kind to him, kinder than an uncle and aunt needed to be, and Thomas would not repay that kindness with ingratitude.

“Of course you wouldn’t, Tom,” Alice went on, putting on the second glove. “You are far too lovely for that. And as you are such a lovely man, you will take me to Charlotte Fairbourne’s this morning, isn’t that so?”

“Right now?” He had just opened a new book.

“She’s got a new hat to show me.”

“I thought you didn’t care for Charlotte.”

“I don’t. But her brother is at home, and I care for him very much indeed.”

“Alice….”

“Thomas. The Montescue name doesn’t carry the weight it once did. If you don’t want me to end up a spinster, I need to work on my own behalf.”

“Mama wouldn’t like that.”

“Yes, well. Mama was engaged to her cousin at seventeen. It’s a new world, Tom, dear. The age of Victoria. And you’ve seen our cousins.” Her expression turned pleading. “Please? You need only to walk me over and collect me later. You can’t sit about the house moldering all day.”

Thomas very much could. Still, he roused himself from his seat and went to fetch his hat.

The Fairbourne house was a short walk down a meandering country lane. The day was fine, warmer than Thomas had expected for early spring. After leaving his sister with her friend, he decided to take the longer way back through the woods. It gave him time to think.

He always had a great deal to think about. His situation made sure of that. Thomas remembered very little of his life in America. He knew he was born in Boston, a big city according to what he had read about it. There were snatches of recollection, here and there, of a difficult early childhood.